Will technology replace hand-painted trail maps? Here’s map-painter Kevin Mastin’s perspective.

This winter I was interviewed by Gregg Blanchard from Slopefillers; here’s the text:

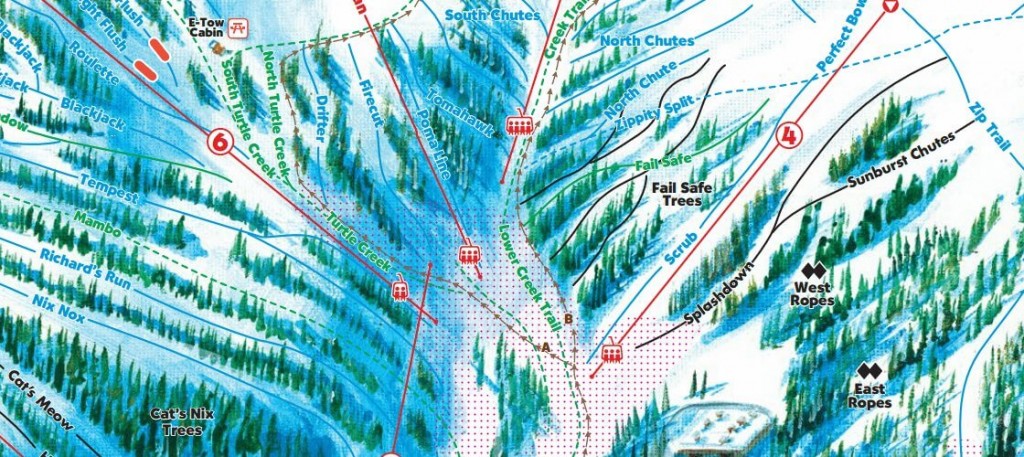

Loveland Ski Trail Map Detail

There are some incredible new technologies within the trail map space.

But behind every block of code or digital overlay is one simple thing: Art. Really incredible art. Art that has remained predominantly hand-painted for decades even amidst the frantic race of web and computer technologies and entrepreneurs trying to “disrupt” everything under the sun.

I wanted to get some perspective on the future of hand-painted maps in a digital world from one of the last trail map artists, Kevin Mastin. Here’s what he said.

–

Gregg: Give us a little bit of background about you, Kevin. Where you grew up, how you got started in art, etc.

Kevin: I grew up here in Leadville. I learned to ski on a very small hill in my backyard, using some of my mom’s and uncle’s very outdated, hand-me-downs: lace-up leather boots, bamboo poles with leather bales, and skis with cable-back bindings. Cooper Hill (Ski Cooper) was our weekend babysitter. There was a bus that ran from town, so we were out there most Saturdays all winter. Loveland was the first “big hill” I ever skied. I skied on our high school team for only a couple years, but I wasn’t great. I skijored for a number of years and was pretty decent at that. As I’ve gotten older I’ve been more into nordic, skate-skiing, and mountaineering.

I’ve always been artistic. My uncle, Ken McGowan, was my high school art teacher. He was very inspiring, very encouraging to me. I knew that I wanted to make a living in art in some manner, but had no idea how that was supposed to work! I learned about the Colorado Institute of Art and toured it when I was a junior. That was my ticket. I went in with the intention of being an illustrator, but quickly discovered that I was surrounded by some amazing talent and that it was a difficult field to break into.

Elmer & Luane McGowan’s Anniversary Clock, and illustration from 1987 while in college at the Colorado Insititute of Art

Out of college, I worked for one of those “Welcome Neighbor” companies, designing vinyl phone book covers littered with ads from local plumbers, car dealers and realtors. It mostly involved typesetting, waxing and pasting up little ads. A highlight of my week would be when the pet shop wanted an image for their ad—instead of using clip art, I could draw a little dog!

My first real break was getting a job for Compugraphic, near Boston, designing typefaces for photo typesetting equipment. These were the very early days of the Mac—literally: Quark 1.0, FreeHand 1.0, PhotoShop 1.0, etc. After 4 years in Boston, creating only vector graphics for the Mac, my wife and I decided to move back home to Colorado, and I nailed my dream job: graphic designer for a ski area – Keystone – very near my home town.

Gregg: What was the first resort trail map you did, when was it, and how did you get that job?

Kevin: Working for Keystone exposed me to ski maps. We were working with Jim Niehues, who I consider “the modern master of the ski trail map.” Jim was updating several of the maps which had been painted by his mentor, Bill C. Brown. Jim painted the artwork, but he did not create the overlays (trail names, lift lines, etc.). This was at the point when some graphic artists were still using press-type, photostats ands acetate overlays. Fortunately, I was already well-versed in creating vector art. So, on my first two maps, Keystone and Arapahoe Basin, Jim painted the art and I did the overlays digitally.

In 1994 Keystone greatly upgraded its mountain biking operation and I got my first opportunity to start a map from scratch—reading the maps, taking the aerial photos, sketching the layout, then painting the mountain—I finally had the chance to paint a widely seen illustration. I worked for Keystone and Vail Resorts until 1997 when I started my own shop.

Gregg: Compared to other art, did you face any surprising or unique challenges when you started painting trail maps?

Kevin: One of the main challenges is presenting the mountain in a way that is intuitive and makes sense to the skier. Map artists are required to “cheat” things around quite bit in order to make things visible. For instance, Keystone comprises three peaks, back-to-back-to-back. The front sides are north-facing and the back sides are south-facing. The resort did not want a map with separate illustrations or insets; they wanted everything in one view. I needed to create “bird’s-eye view” to get everything visible from one angle. It was a stretch, but it worked out.

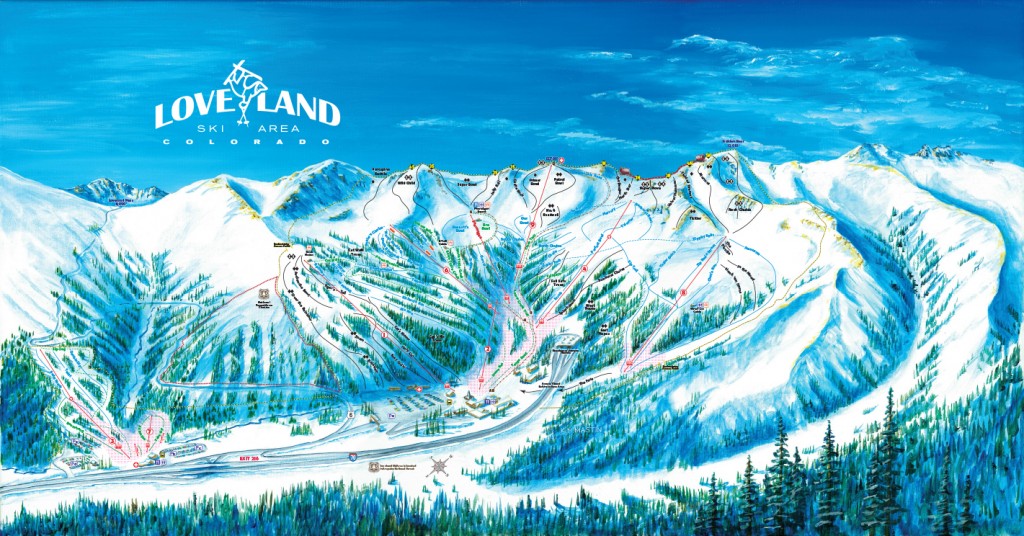

My most recent map, Loveland, was kind of the opposite of Keystone. Loveland is a large basin with slopes converging into a central base area. Their existing map was two images, a North View and a South View, and their skiers found it difficult to piece together. For this painting I created a panoramic, “fish-eye view.”

Loveland Ski Area Trail Map

I consider these trail maps “illustrations” rather than “fine art.” A trick to all of the maps is that the ski areas can’t really be painted too literally. A few examples. Catwalks can be very flat and virtually invisible when looking at the mountain, so the downward slope is exaggerated and the trails widened. The mountains are never as steep and vertical as the skier perceives, so the elevations are almost always extended upward (plus, the marketing folks like it that way!). Also, the paintings need to accommodate all of the labels (lift lines, trail names, legend, compass, etc.) sometimes the trail name itself is longer than the little patch of snow I’m trying paint.

Tangent, but kind of fun: about twenty years ago, I bought an art print from Warren Miller and got the opportunity to meet him and have him sign the print. He surprised me a bit, by asking me why in the heck we always painted the mountain from the base looking up; why not paint it from the skier’s point of view—from the top looking down? I’m good at visualizing things, but I have no idea how I would do that!

Gregg: I love that combination of digital vectors and painting. Let me wrap that idea into what you said about having to “cheat” a little. There are a lot of people trying to create 3D maps using things like Google Earth but I feel many lack the usability of maps like yours. When you look at the progression of technology and the demands of a trail map, will there always be a need for hand-crafted art in trail map creation? Will digital take over? What do you see?

Kevin: I think there’s room for both styles, although aesthetically, I find the digital maps “cold” and not as enticing. I sell quite a number of my trail maps as signed art prints for people to frame and hang in their homes. I’m not sure how many of the digital maps people feel are attractive enough to do that. The colors in satellite imagery are often a bit odd and need to be heavily doctored. The snow is usually too gray, and if you look closely the trees are often parallel to the ground! I use satellite imagery for reference, but most of what is readily available is captured in the summer time (winter, aerial photography is still the best).

It’s also important to remember the the trail map is not just a functional illustration for navigation, it’s a very important marketing and sales piece. The skies are blue, trees are green, the snow is perfect; it’s the signature image of the resort. The traditional, painted map is not going away anytime soon.

Source: Stray Horse Arts (Kevin Mastin)

Last, I’m often asked about maps in formats for use on a cell phone. Whether it’s a digital or traditional illustration, the map should to be loaded on your device before you hit the slopes. There are so many places in the backcountry where you can’t receive a signal, plus batteries fail much quicker in the cold. So, in defense of the printed map—it is safer; I’m a hiker and climber and I’d would never rely solely on a digital format.

Gregg: And along those lines I wanted to get your thoughts on something. On my desk I have a book with hundreds of ski posters from the last 100 years from all over the world. Whenever I flip through it I feel like each decade had a very unique style of art. Even more, a culture that went along with and was reflected in it. Today, I don’t see either. I see very little art. I see very little cohesive ski culture. When you look at ski art over the years, do you see a similar change? Any thoughts on that?

Kevin: That’s a great observation and I definitely agree with you. Think of the volume of vintage ski and travel posters with beautiful illustrations from the turn of the (last) century up until about the 1960s. We have a number of them hanging in our home. Much of the ski art you see today are mimicking the styles from those glory days—I’m not throwing stones, I do it myself.

Where I see the “ski culture” thriving is at the smaller, neighborhood hills. I still feel it in the parking lot at A-Basin and on the deck at Ski Cooper. Skiing has become a very expensive sport and whether you like it or not, it has largely been driven by real estate, and I don’t see that trend changing.

There have been big changes in advertising art in the last 20 years, I’d say mostly driven by the internet, social media, and devices. Photos and videos are quick and cheap and active; illustration is labor-intensive, expensive and static. That said, where you can see the best art being produced is from the younger manufacturers of equipment and apparel. There is some very nice logo and typography work being done. The art is still being created, but it’s not in a magazine or being hung on the dorm room wall, it’s now a t-shirt, a sticker, or the design of a snowboard.

Tagged with: Illustration, Kevin Mastin, Map Design, Ski Trail Map